not substack giving me a rude “post too long for email” warning like i don’t know i’m incapable of brevity!!! i’ll just say this: this is a long read about a lot of things but mostly about aimee mann, whose songs are gifts, and her new album. if you are unfamiliar with her work (no judgment but…), there are lots of links. if you are nice to me i will send you the starter kit playlist i made for my mom. :) yes, i should have been working on the book i am contractually obligated to write instead of this. but i sometimes do not get to choose what my brain decides to fixate upon and be moved by and feel compelled to write about, so please read this so i do not regret the detour! if you are my editor or agent please disregard the above everything is great okay thanks sorry love you bye!!!!

Aimee Mann writes sad songs. A wild generalization, of course, a vast, broad strokes oversimplification of work that is far more complex—but I’ll stop short of saying a gross misunderstanding. Because Aimee Mann writes songs about people, and all their complications. Hers is a catalog of songs in the key of the human condition: meditations on the patterns of behavior we’ve inherited; the ways in which we move through life, tactfully or not; the forced limitations of our own stupid brains and bodies; our fuck ups and failures and fumblings.

And the human condition, when looked at honestly, is inherently sad. You are born into this world and forced to endure traumas big and small, rejections and regrets. People will lie, people will leave, people will hurt you. Sometimes you’ll be the one doing the hurting. The moments of beauty come fast and are few and fleeting. Justice often only exists in theory; awful things will happen to good people, and spoils will go to those who don’t deserve them. As you get older, you’ll have to contend with how little is really black and white, how easy it is for it all to fade out frustratingly to grey matter, lines crossed so many times you don’t even know where the lines are anymore. We are all bruised and broken; some of us just more so than others. Put simply, in Mann’s own words: “It is hard to be a person.”

+

Late at night I lie in bed on my phone, opening and closing apps and opening them again, Instagram, then Twitter, then TikTok, one after the other, refreshing feeds long after I told myself I was actually going to go to sleep. Scrolling in the dark, I can’t escape mental illness, both as a concept, and, in a way, my own. This is what I get for priming algorithms to feed me a diet of memes about overanalyzing and dissociating, ADHD and anxiety, trauma and spiraling and self-loathing I consume while obliterating my sleep cycle. Some of it is helpful, but most of it is funny, garish and crude in a way that feels suited to reflect the ugly wrinkles of our brains.

When I was 20 years old and starving myself, running nearly 50 miles a week, loading myself up on extracurriculars and trying to keep straight A’s with a double major, I would have been terminally mortified if anyone knew I had near-crippling anxiety or an eating disorder. (Everyone knew.) Something wrong? With me? Thank you, but no. Nothing that a little hyper-achievement couldn’t fix. I thought if I just worked hard enough to be better, make myself perfect—a fool’s endeavor—I’d be fine. If people saw who I really am, I would think, stuck in an unending shame spiral. If they realized I’ve just been fooling them the entire time. If they had any idea how stupid and pathetic and gross I really am. I’d just melt out of my skin. Ten years later, I crack jokes online about my perpetual anxieties, about being in therapy, about, well, how hard it is to be a person. Dinners with friends inevitably become roundtable discussions on trauma by the second round of drinks. I write something like this for strangers to read and judge. I am, more or less, a bit more skillful at handling—and far more interested in—the vulnerable, less than perfect parts of reality than I once was. I like to think this growth is a reflection of a lot of work. But if I’m being honest, a lot of it is probably because of the internet.

For those of us who are extremely online, the subject of mental health has moved out from behind closed doors—way out, fodder for casual conversation with friends and strangers alike. I mean, it’s 2021. Is there anyone out there not going through each day with a constant low level hum of anxiety? While many good things can be said about the internet’s role in breaking down stigmas and opening up conversations, there are downsides to flattening a personal and multifaceted experience, to conflating an appropriate reaction to the dumpster fire state of the world with genuine mental illness. Mental health struggles shouldn’t be an internet subculture, or something to hang your entire personality upon, like your astrological sign or Myers-Briggs type. And critics are fair to point out that the rise of #TherapyTikTok essentially makes unregulated social platforms WebMD 2.0, an easy but perhaps inaccurate resource to self-diagnose an affliction we hope will serve as a concrete explanation—or excuse—for our every behavior. But where does the line fall between how much blame can be placed on social media and how much is the fault of society’s long history of silence? After all, when you keep a lid on a conversation for so long, it’s inevitable that it will boil over.

Much has been said about Aimee Mann as an uncompromising and brave musical trailblazer, one who flipped a defiant middle finger to major label mistreatment and went independent at the dawn of the mp3 era. But what goes somewhat unspoken is her artistic prescience. Mann has been writing fearlessly honest, wry songs that don’t just skim the surface of human dysfunction, but dive headfirst into it far longer than it’s been popular enough to be appreciated in meme form. For decades, women like Mann were more turned into punchlines by the proverbial “sad songs” label than made cool girls of the internet. In an era where women reclaimed the label and leaned in to the point that it’s now almost a tired trope, it can be easily forgotten that Mann, and many other women—not just a small select few—had to walk before Mitski or Phoebe or Lucy could run.

+

There’s a classic meme that resurfaces every so often that, at its core, is about deflecting—or relieving, depending on how you want to look at it—despair with humor. “Me w/ tears in my eyes: Time to make a joke,” a letterboard reads. It’s all too relatable, all too real. Whomst among us has not nearly touched the third rail of our emotions and immediately searched for a funny story to tell about it? Laughter isn’t always joy; it’s very often discomfort. Good humor is based in truth; a lot of humor is used as a denial of it.

Aimee Mann often writes sad songs, but they are not maudlin or self-serious. In the span of three minutes, she examines her characters with the insight of a veteran therapist and the studied, yet playful, craft of an adept songwriter who can kick the wind out of you with just the turn of a few carefully composed words. Her songs are unsparing regarding the brutality of life, but never without the sense that she or her characters have made it out to the other side. With scars, maybe, but still intact. There are songs that are sad and songs that are about sad subjects, but they are not always same thing. Most people are not morose all the time, and humor is one hell of a coping mechanism. You know this, I’m sure. I think Aimee Mann knows this, too.1

Life can be sad and hard and messy, but all that inevitably makes it funny sometimes. I mean, it has to be funny. How else would we survive it if it wasn’t? Mann’s oeuvre has its fair share of sad songs that are just plain sad: songs that are bleak (has anyone ever written a better depiction of crippling anxiety and hopelessness than “It’s Not”?), songs that are achingly lonely, songs that are full of shame spirals, self-loathing, and self-destruction. But she has just as many of the about-something-sad-but-not-sad-themselves variety, biting and sardonic, the “me with tears in my eyes: time to make a joke” of sad songs. They are songs about our hapless codependency in toxic relationships, songs about our directionless flailing failing to meet the high expectations we set for ourselves, songs about situations that are just so astonishingly bad that the only thing you can do is wittily twist the knife into those who put you in them.2 “What’s more fun,” she sings on Charmer’s3 intervention banger “Soon Enough,” tongue firmly in cheek, “than other people’s hell?”

+

It’s a Saturday night in Brooklyn and I am watching Aimee Mann sing “Save Me” while the wind whips and the East River laps hungrily at the waterfront, unintentional fill in the sparse three-piece acoustic arrangement. Her most well-known track, “Save Me” is a sad song that is just plain sad, no matter which way you look at it. It is crushingly vulnerable in its simplicity, a slim Exacto knife slicing a precise line across a chest to expose a raw and beating heart.

Some would credit a successful marketing campaign behind the Magnolia soundtrack, the result of which was an Oscar nomination for Mann, with its immense popularity—which, sure—but there’s more to it than that. Few songs become that big off a well-soundtracked film alone, especially one as polarizing as Paul Thomas Anderson’s dizzying three hour long psychological epic. And Oscars aren’t a guarantee of a song’s staying power, either. (When is the last time you thought of “You’ll Be In My Heart?”) No, some songs stick around because they cut through the noise and cut to the chase, dancing across the fine line between universal and specific. A song like “Save Me,” first made popular in 1999, only sustains interest this long4 because it is a song about us. If it came out today, the timeline would be flooded with deflective jokes about it, a Greek chorus of entirely too loud and a personal attack and okay, drag me. We’re in the song, whether we want to be or not. It gets at the heart of the most difficult part of being a person: The dueling desire for someone to see us and the gasping fear that, if they do, they’ll only confirm that the most cruel and awful things we think about ourselves are true, confirm our suspicions that we are inherently unlovable. Some of us are pleading for—daring, even—someone to save us from ourselves. Some of us want to be the person who does the saving. No matter where you land, it’s a little bit sad and a little bit heartbreaking, particularly as the years pass and you realize the song’s inherent youthful naïveté. People cannot save other people, and thinking that they can will only end badly for all parties involved. A song like “Save Me” is a song you’d wish weren’t so perennial if you could get over being so thankful that it is.

More than twenty years after its debut, Mann is older and wearier, her voice tired beyond the pull of jet lag, a tired that feels like the kind that comes at a certain point in life and never goes away, no matter how much sleep you get. Lived in and warm, but not without a bit of an edge. It’s the nuanced sound of experience, of someone who has doggedly worked to survive that which tries to destroy us when the easier option to fold in on yourself is always right there. Hers is a voice that has at times been described as limited in range, but I’ve always perceived it as something different. Even at its most tender and sentimental, it still seems to emerge from behind a steely set of armor, eschewing bullshit and giving it to you straight. The most lilting of notes come from a place of control, pulling taut a leash that’s anchored in a shallow pool of grief. Now it’s saturated in years spent facing the kinds of hardships and heartbreaks life deals all of us, the kinds we never anticipate but must choose to persevere through anyway. “Save Me” will always threaten to break your heart, but now, as we emerge from an isolating infinite present of forced individualism, the song—particularly this version, slower and more elegiac—seems poised to shatter it entirely. Mann is not the only one who is tired.

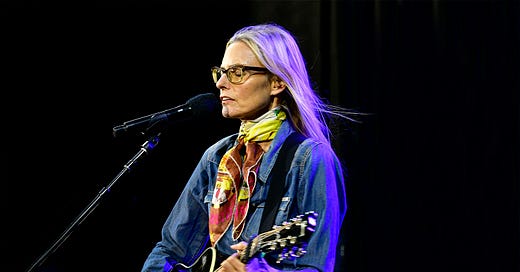

The weather was beginning to turn. Earlier that evening, Mann, dressed in jeans and a denim shirt, her signature neck scarf a cheerful sunny yellow, shivered while in conversation with The New Yorker’s Atul Gawande. Mann has a history of being refreshingly forthcoming and eloquently straightforward about difficult subject material, be it early music industry struggles or her own mental health and past trauma. But no matter how comfortable you get with the uncomfortable, there is a distinct difference between candid conversations in private—where a certain intimacy is afforded a subject and their interviewer, and the combination of time and medium puts distance between yourself and the audience—and in public, where an audience is watching—consuming—you in real time. When Gawande, who is a fine writer and surgeon, but can be an awkward interviewer, bluntly asked Mann about her tumultuous childhood, she gave him a brief anecdote5 before chuckling nervously. “So that was fun. That was great. That probably didn’t fuck my life up at all,” she said, a tersely deflective joke no one could bear to laugh too hard at. By then a stagehand had appeared from the shadows to offer her a plaid throw and she wrapped herself in it, giving her interview from underneath its protection.

The lush green summer was dying all around us: air chilled, sky grey, leaves turning. Fall is a time for dying; we are used to this, unfazed by the annual tradition. It is temporary, we tell ourselves as we unpack our SAD lamps. Relief will come. Life will begin again in six months, give or take. I pushed back the knowledge that the only reason we were sitting outside in the cold to begin with was because we have spent the past 20 months swallowed whole by the constant presence of death, treading water with no island to rest in sight.

Some sad songs are just sad. Sometimes there’s no irony to point out, no joke to be wrestled out that’s funny enough to distract us from the brutal wreckage. Sometimes sad songs are just blankets, and all you can do is accept their warmth.

+

I’ve buried the lede here. This is all a long-winded way of saying that Aimee Mann has a new album out, and it is full of sad songs—both kinds. An adaptation of Girl, Interrupted, Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir about her stay at McLean Hospital in the late 1960s, the sad situation part takes care of itself. With source material like that, you can choose to exploit the sadness, to wallow in its potential for melodrama, which is what plenty have done. Kaysen herself has been vocal about her disappointment with the ways in which audiences have misunderstood her work. She meant to be “an anthropologist in the loony bin,” not the patron saint of the sad sick girl memoir boom. The other option is to see it for the complicated thing it really is, write tragedy and comedy in the same breath. You can sweeten the poison pill a little, make use of the gallows humor Kaysen deploys in her novel with sharp toothed lines like “every window in Alcatraz has a view of San Francisco,” which is exactly what Mann does.

The joke is that only Aimee Mann could score a Broadway show about women confined to a mental institution. It’s a joke that Mann—who literally beat everyone to the punchline once before when titling her 2017 Grammy-winning album Mental Illness—is in on. Queens of the Summer Hotel, comprised of music written for the currently on-hold Girl, Interrupted show, is, in a sense, a continuation of Mental Illness, both musically—moving away from a vintage soft rock soundscape of acoustic guitars and mellotrons and towards lush woodwind and string arrangements backing piano driven tracks—and thematically, addressing the most harrowing parts of sanity head on.

Queens of the Summer Hotel is an album full of trouble, crises and compulsions, suicide and self-harm; troubles encountered in the real world and the troubles suffered at the hands of those who are supposed to protect you. Across its fifteen tracks, she masterfully weaves small tales about desperation and dissociation and depression, about shame and trauma and the realization that some girls are just born happy and some are not. It’s the kind of subject matter she handles best: navigating a path through the dark, thorny brambles of being alive. All the while, the gravity of the situation hangs thick in the air, impossible to ignore, sometimes indulged in, but just as often given a blunt, deadpan acknowledgement.

It’s not an easy album to love. At its most stunning, it occupies elegant Bacharach/David territory, but, periodically, it can get slightly stuck on the way there in the theatricality of it all.6 It’s not an original cast album—the show’s development is still up in the air—but it doesn’t entirely work as an independent concept album, either. Without the context of character development or visuals likely established in the show’s book or staging, a few of the tracks, while pleasant to listen to and beautifully orchestrated, don’t quite stand on their own outside of an unknown theatrical universe. Songs like “Give Me Fifteen,” “Home By Now,” and “In Mexico” are sharply written, but can feel slightly burdened by their intended on-stage expository responsibilities; the hypnotic interlude “Checks” and its reprise, which struck me as an allusion to OCD,7 are actually meant to be the soundscape of hospital rounds. But the through-line is Mann’s singular storytelling ability. Queens may be difficult for more pop/rock purists to view as a purely canonical album unless you happen to exist in the intersection on a Venn diagram of Aimee Mann fans and musical theater fans; its sound is an acquired taste.8 But it is the kind of unique and unconventional album she has the freedom to make and release as a truly independent artist. And in the end, it nets out strongly on the side of studied craftsmanship and exquisite world building by someone who clearly respects and appreciates musical theater’s lineage. Mann has always had a talent for putting herself in others’ shoes, at making personal the stories of addicts and hoarders and burnout teens9 alike, and her deeply empathetic understanding of the cast of characters at McLean is felt. She fully inhabits each and every one of them, be it the sexually abused bulimic or the dismissively sinister male psychiatrist, with conviction, gentleness, and generosity.

When I say Queens is not an easy album to love, I don’t mean that it isn’t very good, or that it doesn’t endear itself to you the more time you spend with it, the more you work to understand it and meet it on its own terms. Repeated listenings become more rewarding. There’s a notion that we shouldn’t have to make any effort to enjoy art, that if something is good, we will have an immediate reaction of appreciation. It’s an embarrassingly lazy and incorrect assumption, one fueled by the high speed collision of art and capitalism. In an economy driven by hot takes and short attention spans, there can be no room to think in detail. There’s always something new to listen to, another new release eclipsing last week’s darling. Time is a luxury few of us have anymore.

The irony is that for all the wishing I’ve done that I was free of any difficulty myself, I love when a piece of art or music challenges me, when it isn’t an easy, pleasant swallow but instead gets lodged somewhere in the back of my throat. No one is easy to love, so why should an album be? There’s something special about art that is intriguing and compelling enough to make me want to swim around in its world for awhile to figure out what I think about it, piecing it together like a puzzle whose edges will reveal themselves to me in their own time. In a way, this matter of consumption feels fitting for the subject: Look beyond the veneer of a girl, past her charming first impression. Invest a little time and get to know her knotty inner workings.

+

There’s a lot of watching in Queens of the Summer Hotel. Women watching other women; men watching women; women floating outside their own bodies, watching themselves—and Aimee Mann, our storyteller, watching them all. Throughout the album, Mann deftly flits out of the second person and into the first and back again, sometimes within the same song. It’s a clever framing device, often used to convey the protagonist’s dissociation from herself, but it does something else, something even larger. Though the lack of stage context can occasionally hinder Queens, it can just as often unexpectedly benefit it, unlocking a new way to interpret the material, if you tilt your head just right. Consider: Floating above the traditional protagonist-as-narrator structure is something more metatextual. There’s implicitly another person, an omniscient, all-knowing narrator, the architect of this narrative, observing these disparate stories, stitching them together and presenting them to us, at times chiming in.

“I know what you think: ‘This happens to other girls,’” she sings on gorgeously harmonic album opener “You Fall” over a driving piano riff. It’s the sound of striving striving striving, attempting to bury your feelings with busyness, but by the end, it slows. All that running is a treadmill; you’re bound to wear yourself out. And then what? “You’re strong, but, lord, who’s really that tough?” Mann asks. “You’re not made of such unbreakable stuff.” It’s a line too insightful to be a protagonist’s self-observation; very few of us possess the astute self-awareness needed to have such a clear perception of ourselves or our situations while in the moment, especially when the moment is a breakdown. No, it’s the kind of observation only an outsider is capable of making, the voice of someone trying to talk some sense into you, catch you before you go too far. It’s the tell, the nod that Mann is the one telling this story before stepping into the background, where she lets everyone else’s stories take center stage, refraining from offering her own commentary until the album’s twin endings.

“When nothing keeps you together, when nothing is holding you in, you’re a balloon, and all the world’s a pin,” Mann sings on the penultimate “You’re Lost.” We fracture ourselves so easily these days. As public life becomes increasingly public, our personal lives become material for the slow serotonin drip of external validation. When your sense of self is reliant upon an audience, the slightest misapprehension may knock you off your axis. So we keep going until we’re unsure if who we are is who we think we are, or just the performative version. Sometimes a person doesn’t break in one fall; sometimes it’s the cumulation of a series of small fractures spiderwebbing out, ledges on the way to rock bottom. “No scaffold or frame or structure, no bones beneath your skin. Where do you end and where does she begin?” she prods, gently, but with a gnawing knowingness that forces a person to look at their life honestly. It is the simultaneously wanted and dreaded response of “no you’re not” from someone who knows your “I’m fine” is a lie, one Mann carries into the devastating, illustrative finale “I See You.”

Stepping out from behind the curtain, she is no longer embodying a character in Girl, Interrupted’s world, no longer acting as its architect or light commentator, but firmly inserting herself into the narrative: “There is a girl out with the tide, empty as the sky—I see you. Dead to the world, frozen inside, drier than an eye—I see you.” Her voice is direct and humane at once, an outstretched hand to reach for, a lighthouse in the inkiest of night skies. She has been one of those girls, or close enough, has known girls like that. The sharpest edges of our interior worlds are not as rare as we believe them to be.

“You want to disappear and just not be, but I can see,” she sings. And isn’t that what we want most of all? Some sort of acknowledgement of our reality, some sort of human connection? How we work for it, all those hours reading and watching and listening for a shared experience, all that time spent searching for ourselves in others. How we long for some sort of human X-ray, someone who can see who we are better than we can, spot the things we keep buried beneath our shiny facades; a corroborating witness to experiences others dismiss. It’s why we love the wrong people, why we impose too much emotional responsibility on friends who were never meant for it, why we cling too long to relationships even as they begin to sour. We make so many jokes about the mortifying ordeal of being known, but is it all just a shallow defense? Wanting to be seen is a humiliating, dangerous desire, a trust fall off a cliff. Better to pretend we don’t want it at all. With recognition comes the possibility of rejection, the chance that the things someone else sees in us won’t be good like we hoped they would be. The inevitably of betrayal waits for us at every turn.

But Mann’s perceptiveness is one of compassionate acceptance, almost urgent in its asking you to trust in its wisdom. She insinuates that things can get better, but she doesn’t promise it, doesn’t tell us that it will all be okay in the end. That would be a lie. Life does not resolve itself like a narrative, all loose ends cleanly tied up with a happy ending. But she does tell us whatever it is we’re going through, someone else will acutely understand; we don’t have to weather it alone. In some ways, it’s a sister song to “Save Me,” a role reversal, if you will, someone singing from the vantage point of the other side. It’s the kind of assurance I spent so much of my twenties searching for.

There’s another kind of sad song: The kind of song that is not explicitly sad, but can move you to tears anyway. Maybe it’s because it’s hopeful or comforting, some sort of unconditional acceptance we aren’t capable of extending to ourselves, the kind of solidarity we can only take from a total stranger.

+

“Music, to me, is such an intimate [thing]. Somebody’s talking to you in this very intimate way, and I want to feel that that person could possibly understand complicated feelings that I have,” Mann said in 2017. “And I want people to listen to my stuff to feel that way about me, that I could be somebody who would understand their complicated feelings.”

###

i love how up top i said you had to be nice to me to get this; that’s a lie. here’s an aimee mann starter kit for you all to enjoy if you made it this far. for the real “if you’re nice to me” treat, i’ll send you my favorite tracks by aimee’s early 80s post-punk band—we contain multitudes!!—the young snakes

if you liked this and are new here and maybe want to read more, all archived posts live here.

my dms / replies / emails / calls and textses* are always open. say hi. (*do not call me)

subscribe and tell ur friends!

okay that's it that's the end thanks bye

I cannot stress enough that even though she writes some dark shit, Aimee Mann, truly, is so very funny. Please log onto YouTube and see for yourselves.

See also: “Julie, Julie.” Written for Difficult People, it isn’t technically canon, but further proves her grim sense of humor. You can’t really beat lines like: “Julie, to follow your bliss just remember that this is a journey / I’d rather ride on a gurney”

If you want Mann at her most pitch black, bone dry comedic, start here.

On Spotify alone, “Save Me” has more than 23 million plays, while the rest of Mann’s discography averages in the mid-high six figures.

Mann’s parents split up when she was three. Subsequently, her mother and her new boyfriend kidnapped Mann and took her to England, where she lived for nearly a year until she was reunited with her father. She did not see her mother again until her teens.

Though a preview of the tracks’ live acoustic arrangements strikes a more familiar (and intimate) musical sensibility.

Where my anxious lock checking party people at???

Acquire some taste, as the meme says.

I am so sorry for this, my most gratuitous footnote, but I am legally obligated (no) to say: Personally, I would be so fucking embarrassed if I were Jimmy Iovine or any other record exec who listened to Bachelor No. 2 and told Aimee Mann she didn’t have a single when “Ghost World” was RIGHT THERE.